West Oakland: Mapped by Destruction

May 23, 2023 Habitat News

Alameda County: A Demographic Overview

Alameda County is home to “one of the most vibrant and diverse metropolitan areas in the nation,” but like much of the Bay Area, “its racial diversity is not reflected in most of the communities within the county.” Just a few places within the county might be considered somewhat integrated. Much more common are “racially identifiable cities and enclaves,” like Piedmont, Pleasanton, and Livermore that “typify the heavily white suburb,” or the southern county’s Fremont and Union City’s high proportions of Asian residents, or Hayward’s concentrated Latino population.

The city of Oakland is “exceptionally diverse,” but it encompasses “some of the most segregated neighborhoods in the Bay Area” – particularly for Black residents. [i] And it’s home to one of the oldest and most storied neighborhoods in the city, once a bustling center of Black life, culture, and commerce – West Oakland. It’s a community close to our hearts at Habitat East Bay/Silicon Valley, just a few minutes away from our headquarters, site of the 12 Habitat houses at Palm Court, and home to some of our staff members. To know its history is to be more determined than ever to invest in its future.

West Oakland: A City Within a City

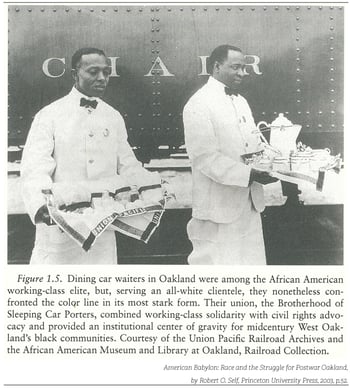

We cannot begin to encapsulate the million stories contained in the greater story of West Oakland. There were the ones that will be familiar to many. The transcontinental railroad’s western endpoint at the harbor. The seat of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on 5th Street, home of the first Black-led labor organization in the American Federation of Labor. Maya Angelou’s brief mid-war stay in the neighborhood. The hub of the Black Panther Party.

We cannot begin to encapsulate the million stories contained in the greater story of West Oakland. There were the ones that will be familiar to many. The transcontinental railroad’s western endpoint at the harbor. The seat of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on 5th Street, home of the first Black-led labor organization in the American Federation of Labor. Maya Angelou’s brief mid-war stay in the neighborhood. The hub of the Black Panther Party.

But there were, too, the smaller stories, an extraordinariness in the everyday that made West Oakland vibrantly unique, what one resident called a “city within a city.” [ii]

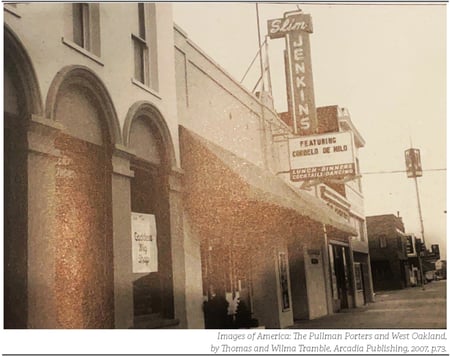

The neighborhood was a tapestry in the years before World War II, “a mix of immigrants: Germans, Italians, Jews, Gypsies, Scots, Portuguese, English, Welsh, Norwegians, Finns, French, Mexicans, Japanese, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Irish, Filipinos, and Chinese,” recalls Ruben Llamas in Eye from the Edge: A Memoir of West Oakland, California. While it was certainly not untouched by racism – Llamas recalls Latinos needing to defer or even leave the soda fountain counter when White people were present, or understanding that some housing was not meant for people of color – his youthful memories are of shining shoes, of the sisters in their gray habits at the neighborhood church, of catching double features on an active 7th Street filled with Black-owned businesses and the din of shopping and music and passing trains. [iii]

A Center of Black Cultural Life

As the war loomed and broke, though, many White families left West Oakland for the less dense, more residential reaches of Oakland. For these families, mortgages backed by the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans' Affairs enabled them to “carve new working-class space outside of the older parts of the city.” Meanwhile, “World War II transformed few places in the East Bay as dramatically as West Oakland,” with an influx of “tens of thousands of African American migrants from the southern states” settling in the neighborhood for wartime work. Due to housing segregation, there was “such a small part of the city that black folk could live in that they were sleeping on top of each other,” remembered one wartime resident. So concentrated was the Black population in West Oakland at the time that it became “the center of midcentury East Bay African American social life and politics.” [iv]

Wartime West Oakland was booming. ”By the middle years of the war, African American West Oakland was thriving on the income of its thousands of new African American residents,” Robert O. Self writes in American Babylon. Seventh Street was a flourishing corridor of Black-owned businesses and services: “Slim Jenkins’ jazz club on Seventh and Wood streets headlined a famous (now legendary) nightclub scene; women’s clubs, churches, and fraternal lodges thrived; and the district developed a special sense of transplanted community” with the settling of so many southern migrants.

Rail, freight, and manufacturing anchored the Black working community, and “African Americans in West Oakland developed a unique geographic relationship to work.” Rather than traveling through “hostile white neighborhoods to reach jobs” – as was the case in other large industrial cities – “work, in many ways, came to them.” And it was lush with connections to the wider world. Pullman porters branched outward by rail throughout the country and brought Black newspapers back from far-flung cities. Ship workers from all around the world mingled at the docks with the longshoremen of West Oakland. “Despite the vicious racism that confined black workers to the worst and most menial jobs… This dual experience, of immediate spatial confinement in West Oakland and of expansive connections to and exchanges with a much larger world, became the foundation of Oakland’s African American working-class culture.” The community’s women performed a range of paid and unpaid labor and civic engagement, inside and outside the home, and knit together a rich social fabric that “gave West Oakland’s bustling streets and neighborhoods a sense of safety and familiarity while quietly holding families and homes together.” [v]

The End of the War and the Beginning of Blight

Once the war ended, however, “you could see the neighborhood changing,” remembers Llamas. His friends’ families were moving out of West Oakland, and “the city was closing down the old housing projects… Seventh Street started to lose more of its luster.” [vi]

The end of the war sapped West Oakland of its wartime production jobs, and rail travel fell out of fashion with the rise of automobiles. The Key System, whose intra-city trains had carried so many into the neighborhood, declined post-war and stopped bringing passengers out to 7th Street to patronize local businesses. One resident remembers that “the businesses closed down, the streets looked shabby.” Meanwhile, Black homeowners in West Oakland – a “redlined” neighborhood – found banks disinclined to offer them the repair loans they needed for the upkeep of their homes. [vii]

So, it was not long before “urban renewal” was on the table. “City administrators spoke as if renewal and redevelopment were synonymous,” writes Self, “but local residents knew the difference between low-interest loans and bulldozers: the former meant restoration and community improvement, the latter symbolized what became widely known nationwide as ‘Negro Removal.’” [viii] The latter was the path taken in the years that followed, reshaping the community through eminent domain – by which the government siezed residents' property for public use.

The "Renewal" of West Oakland

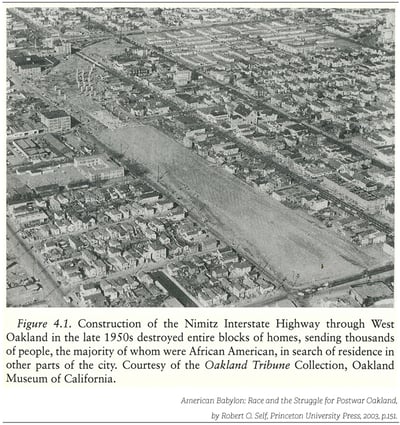

First came the freeway. The vision for Oakland’s freeways began in 1937. “Although no one knew the full ramifications at the time, the seeds for metropolitan decentralization and Oakland’s decline were being laid out in wide ribbons of freshly poured concrete,” writes Mitchell Schwarzer in Hella Town. [ix]

First came the freeway. The vision for Oakland’s freeways began in 1937. “Although no one knew the full ramifications at the time, the seeds for metropolitan decentralization and Oakland’s decline were being laid out in wide ribbons of freshly poured concrete,” writes Mitchell Schwarzer in Hella Town. [ix]

In 1957, the double-decker Cypress Structure was cut through the heart of West Oakland, and it “functioned like a wall, cutting West Oakland in two. Dwellings, businesses, a YMCA, and an orphanage were demolished or moved.” Traffic noise and air pollution filled the air. [x] Where Black homeownership, culture, commerce, and community had thrived, the freeway ripped much of it up by the roots – and it was only the beginning.

A few years after that, hundreds of homes in a 20-acre swath were razed to build the US Post Office’s regional distribution center, nearly a million square feet in size, on 7th Street. Meanwhile, the Oakland Redevelopment Agency undertook a series of projects aimed at urban renewal, and vast areas of West Oakland were cleared. In the end, “because the program resulted in net housing losses, it made it more difficult for poor Oaklanders to obtain housing. During the 1960s, depending upon the estimates, between 5,100 and 9,700 housing units were lost in West Oakland alone.” In the efforts to “renew” West Oakland, Schwarzer says, “the cohesive black community of West Oakland and its commercial spine, 7th Street, was torn asunder.” [xi]

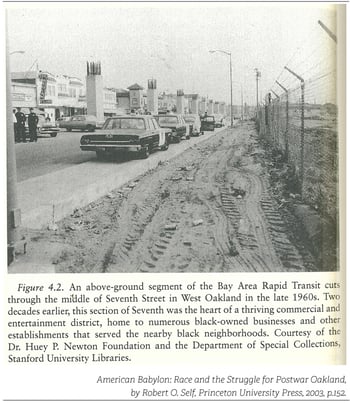

Then in 1974, service opened at BART’s West Oakland station, which “decimated” half of the business district along 7th Street. [xii] The trains whistled loudly on a massive elevated set of tracks, over a desolate, shadow-darkened ghost of what had once been the neighborhood’s heart. In 1989, the Loma Prieta Earthquake ripped through the Bay Area and 42 people were crushed in a failure of a portion of the Cypress Freeway. Broad-laned Mandela Parkway took the place of the elevated freeway, but few of the vibrant business and community amenities envisioned by neighborhood residents were realized.

Then in 1974, service opened at BART’s West Oakland station, which “decimated” half of the business district along 7th Street. [xii] The trains whistled loudly on a massive elevated set of tracks, over a desolate, shadow-darkened ghost of what had once been the neighborhood’s heart. In 1989, the Loma Prieta Earthquake ripped through the Bay Area and 42 people were crushed in a failure of a portion of the Cypress Freeway. Broad-laned Mandela Parkway took the place of the elevated freeway, but few of the vibrant business and community amenities envisioned by neighborhood residents were realized.

West Oakland saw the residences of so many homeowners – homes that held decades of families’ accumulated wealth – seized and razed. These displaced families were left without adequate compensation to find other housing in the area. The community saw neighborhoods gutted at their middles, social fabrics torn irrevocably. It saw trains and cars roar past, cutting quickly through what was once a destination. For a “generation that came of age in the postwar decades in the midst of this physical destruction,” that ruin has “shaped people’s memories and emotional maps of West Oakland.” [xiii]

A Fairer Future?

Today, the face of West Oakland continues to change, though elements like housing prices – rather than eminent domain – are doing the sculpting. Habitat’s mission to make (and keep) homeownership affordable and equitable is one piece of a much bigger effort needed to push back against the prevailing tide in this community and so many others, but we believe it is a critical one.

Another piece is an awareness of this history and the context in which we work. As we've explored over the course of this series, we work in a housing landscape shaped by decades - centuries - of injustice. The homes and livelihoods of Black people and people of color have been systematically destroyed, if not altogether denied the opportunity to take root, and the effects of this inequity play out in the communities we serve to this day. It's a mindfulness we hold as we build and preserve affordable homes, as we serve with intention to ensure those systemically barred from homeownership due to structural racism have a chance to achieve this cornerstone of stability and wealth-building. To secure a stake in the communities they love. To plant deep roots and grow strong legacies in the soil of a new housing landscape.

West Oakland, Milpitas, Richmond, and everywhere we serve – all of these stories are a challenge to hold ourselves to the ideal of the Fair Housing Act. An insistence on not just what is legal, but what is right. An invitation to write a more equitable chapter, together. You can join us by remaining engaged in this inquiry of our history, and committed to the work that builds a world where everyone has a decent place to live.

[i] Menendian, Stephen, and Samir Gambhir. Publication. Racial Segregation in the San Francisco Bay Area, Part 1. University of California, Berkeley, October 30, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/racial-segregation-san-francisco-bay-area-part-1.

[ii] Self, Robert O. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

[iii] Llamas, Ruben, and Terry Burke Maxwell. “Busy Boyhood.” Chapter. In Eye from the Edge: A Memoir of West Oakland, 7–28. Carmichael, CA: Earth Patch Press, 2012.

[iv] Self, Robert O. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

[v] Ibid., 49-57.

[vi] Llamas, Ruben, and Terry Burke Maxwell. “Eyes… and Ears.” Chapter. In Eye from the Edge: A Memoir of West Oakland, 7–28. Carmichael, CA: Earth Patch Press, 2012.

[vii] Self, Robert O. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

[viii] Ibid., 140.

[ix] Schwartzer, Mithcell. Hella Town: Oakland's History of Development and Disruption. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2022.

[x] Ibid., 174.

[xi] Ibid., 242.

[xii] Ibid., 194.

[xiii] Self, Robert O. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Join the Conversation

Leave Us a Comment!

We love hearing from our community. Let us know what you think by leaving us a comment below.