Fair Housing: Looking Back to Build Forward

April 24, 2023 Habitat News

Each April, Habitat for Humanity celebrates Fair Housing Month, a commemoration of the federal Fair Housing Act passed on April 11, 1968. What has become known as the Fair Housing Act was Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act signed by President Lyndon Johnson–which “prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex, (and as amended) handicap and family status.” The Fair Housing Act’s faltering passage through Congress shifted when on April 4, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated; President Johnson used the tragedy of losing Dr. King – a man so strongly associated with the cause of fair housing – to galvanize the support needed to pass the Act ahead of his funeral. [1]

The Fair Housing Act is, indeed, something to celebrate. To codify these values is a key milestone, and a vital turning point in our housing history. However, we cannot mistake celebration for complacency. So, we mark this Fair Housing Month with a thoughtful look at the path fair housing has taken here in our service area of Alameda, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara counties – to examine what injustices have shaped our communities and to move forward with intention so that we may build a more equitable future.

This means taking an unflinching look back at what made the Fair Housing Act necessary – and recognizing that the work is not nearly complete.

"If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?"

It may be tempting, here in the San Francisco Bay Area, to dismiss racist housing policies and practices as an unfortunate – but distant – problem. However, Richard Rothstein starts his seminal book, The Color of Law, with a chapter entitled, “If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?” Rothstein points out that our region is thought of as among the nation’s most “liberal and inclusive,” yet “if the federal, state, and local governments explicitly segregated the population into distinct black and white neighborhoods in the Bay Area, it’s a reasonable assumption that our government also segregated metropolitan regions elsewhere and with at least as much determination.” [2]

Further, “many exclusionary housing policies now common across the United States originated in the Bay Area” as shared by authors of Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area. [3] So, we cannot ignore the uncomfortable truth that our home communities have not been immune to racist housing policies and practices – quite the opposite.

”We, all of us, owe this to ourselves. As American citizens, whatever routes we or our particular ancestors took to get to this point, we’re all in this together now."

- Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law

We live with our own racist housing history, but the Fair Housing Act has also not put an end to the matter. Unfortunately, this history has cast a very long shadow. These injustices were deeply and systemically ingrained and endorsed. “Today’s residential segregation… is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation, but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time,” argues Rothstein. [4]

Roots, Race, and Place localizes this reality: “The lasting impact of these historic processes is clearly evident in the Bay Area, where racial residential segregation levels have persisted and, by some measures, even worsened since the 1970s.” Its review of our area’s history finds that “racism reinvents itself, proving to be dynamic, generative, and fluid, yet also remarkably durable and entrenched.” [5] Housing injustice is something that not only endures because of pre-Fair Housing Act policies, but has evolved in various ways to withstand the Act.

Segregation and Inequity in the Bay Area

We must, too, understand this history as not simply the result of a few bad actors, but an intentional, systematic record of segregation and inequity. Our area's history was born of atrocities that dispossessed Indigenous people of their land and far worse. State-enshrined exclusionary housing continued in the area, with the “alien land laws” of the early 1900s – not repealed until 1956 – designed to restrict the property rights of Asian populations. And, of course, the compulsory internment of Japanese Americans during World War II tore thousands from their property and communities.

The Second World War brought with it as well a huge migration of Black Americans to the Bay Area, many coming from the South in pursuit of the economic promise of wartime and post-war manufacturing jobs. A wave of migration from 1940 to 1970 saw an increase in the Bay Area’s Black population by over 300,000 people. [6] In Oakland alone, the Black population rose from 8,462 to 21,770 people between 1940 and 1945 – an increase of over 157%. Richmond saw an even more pronounced shift, with its Black population climbing by over 2,000% in those years, from 270 to 5,673. [7]

Segregated Public Housing

With the changing demographic landscape came a concerted push for segregation. Incoming Black migrants were met with both virulent discrimination on a social level, and overt governmental discrimination – including explicitly segregated public housing created by the federal government in response to a sudden and profound housing shortage. And as so marks the history of segregation, separate certainly did not mean equal. The inequity was compounded by the fact that White residents were afforded many private housing options not available to Black residents. Those options offered many White families a path out of public housing, while ”Black households became the majority of public housing tenants in Berkeley, Oakland, and Richmond… These residents were essentially trapped, as racial discrimination continued to limit their housing options.” [8]

With the changing demographic landscape came a concerted push for segregation. Incoming Black migrants were met with both virulent discrimination on a social level, and overt governmental discrimination – including explicitly segregated public housing created by the federal government in response to a sudden and profound housing shortage. And as so marks the history of segregation, separate certainly did not mean equal. The inequity was compounded by the fact that White residents were afforded many private housing options not available to Black residents. Those options offered many White families a path out of public housing, while ”Black households became the majority of public housing tenants in Berkeley, Oakland, and Richmond… These residents were essentially trapped, as racial discrimination continued to limit their housing options.” [8]

Urban Renewal

With this fact came widespread public opposition to public housing. A case in point is the history of Albany’s Codornices Village, “the site of one of the most racially charged housing battles in Bay Area history.” Codornices Village’s proposed 1,900 public housing units prompted the City Council to warn of “an undesirable element” that carried the threat of integrated schools – which would make Albany “like south Berkeley." It was ultimately built – and segregated, with White tenants in “more desirable units on San Pablo Avenue” and Black tenants “shunted to the west side of the project, next to the Southern Pacific railroad tracks.” However, post-war public backlash made it a racial flashpoint, and in 1956 its nearly all-Black residents were forced out and almost all the units demolished." [9]

The opposition to public housing culminated in a 1950 ballot measure which stands to this day: Article 34, which “mandate(s) a local voter referendum for any federally or state-financed housing for ‘persons of low income.’” This amendment has “created a major barrier for affordable housing in the Bay Area” and is the reason multiple public housing developments were blocked. Article 34 withstood a challenge before the Supreme Court in 1971 with James v. Valtierra – a challenge brought on the grounds that preventing low-income housing developments unfairly impacted people of color; Article 34 stood because the Court did not see evidence of race-based intent. “By establishing the principle that unconstitutional racial harm must be intentional and explicit,” argues Roots, Race, and Place, “the decision was a legal turning point that severely undermined recently enacted fair housing laws.” [10]

And the push against public housing built during the war brought a wave of “demolition and federally funded urban renewal in the postwar era that displaced thousands and particularly devastated major centers of Black culture and community… Due to these consequences, urban renewal became known nationally as ‘Negro removal.’” Mass displacement was conducted under the guise of this renewal, including that of a robust West Oakland community and “communities of color in the South Bay. Santa Clara County officials directed three interstate highways and an expressway through east San Jose, which ‘involved the bulldozing of entire neighborhoods with high concentrations of Spanish-speaking people’” – and these homes were replaced at a fraction of their previous numbers and often sold at prices the former residents could not afford.[11]

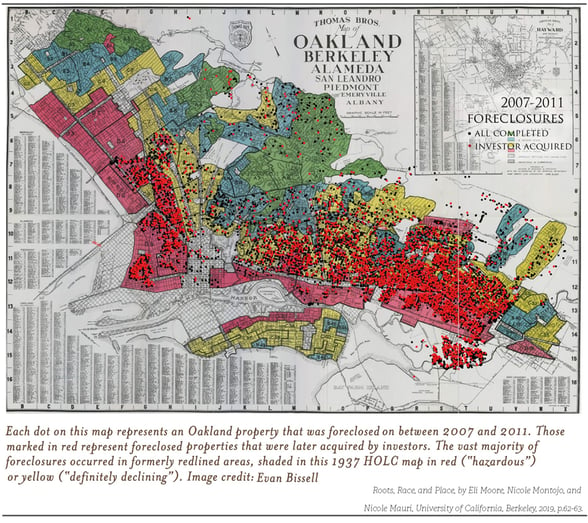

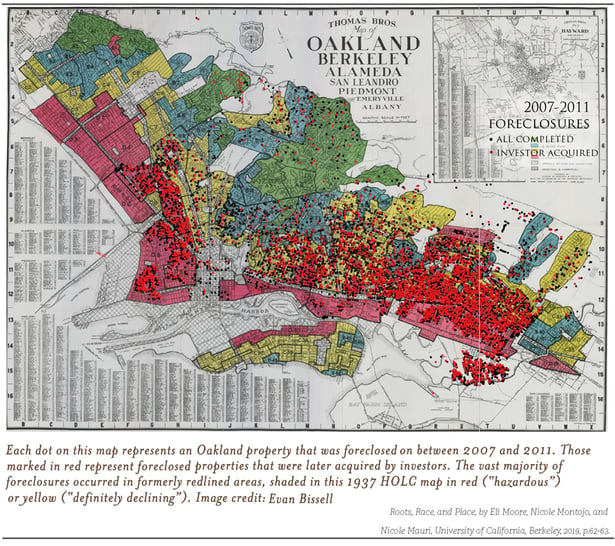

The government invested in discriminatory housing practices through government-backed mortgages – or, in the racist distribution of them. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was born in 1933 to address a looming default crisis during the Great Depression. The HOLC would purchase mortgages from homeowners facing foreclosure, and they would offer new mortgages with beneficial terms. The HOLC is an agency whose name is now closely associated with the practice of “redlining,” whereby the agency created maps of major American cities – including Oakland, Berkeley, Albany, Alameda, Emeryville, Piedmont, San Leandro, and San Jose – that were color-coded by their perceived risk of default. These colors, of course, accounted for the racial make-up of the neighborhoods they outlined. Red – the riskiest designation – was applied to neighborhoods with Black residents, “even if it was a solid middle-class neighborhood of single-family homes.” A solidly White middle-class neighborhood, though, was deemed the low-risk color green and worthy of being “rescued.” [12]. These maps were used to inform a breadth of investment and lending practices, underlining pervasive housing injustice.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created in 1934 to offer first-time homeownership opportunities to the middle-class, insured mortgages at 80% of home purchase prices, and these were based on the FHA’s own appraisals – and “because the FHA’s appraisal standards included a whites-only requirement, racial segregation now became an official requirement of the federal mortgage insurance program.” And so, homeownership was systematically kept out of reach for people of color. [13]

Zoning

Racially exclusionary housing has yet another face: zoning. “Bay Area cities lead the country in creating zoning regulations motivated by racial exclusion,” according to Roots, Race, and Place. Overt racial zoning was legal until 1917 – with San Francisco attempting to pioneer the practice in 1890 as the first city with an ordinance barring Chinese residents from certain neighborhoods. Even after the practice was ruled unconstitutional, “some localities throughout the United States continued to enforce racial zoning,” while other segregationists “began advocating for ‘comprehensive zoning,’” and still others “turned to private deed restrictions.” [14]

Racially exclusionary housing has yet another face: zoning. “Bay Area cities lead the country in creating zoning regulations motivated by racial exclusion,” according to Roots, Race, and Place. Overt racial zoning was legal until 1917 – with San Francisco attempting to pioneer the practice in 1890 as the first city with an ordinance barring Chinese residents from certain neighborhoods. Even after the practice was ruled unconstitutional, “some localities throughout the United States continued to enforce racial zoning,” while other segregationists “began advocating for ‘comprehensive zoning,’” and still others “turned to private deed restrictions.” [14]

In Berkeley, the modern iteration of zoning was born. A 1916 ordinance created eight land use zones– with explicitly racial reasoning, like seeking to exclude Asian and Black businesses. The ordinance is thought to be the nation’s first to establish a zone exclusively for single-family houses, and Berkeley’s measures were lauded statewide in the California Real Estate magazine ten years later for their “protection against invasion of Negroes and Asiatics.” [15]

Roots, Race, and Place posits that Berkeley’s zoning established a national trend that endures today. “Berkeley’s zoning scheme and much of the Euclidean zoning that swept the country were early examples of implicitly racist policy design, evidenced in the publicly stated reasons for the policies, and their impact” – which includes an association between cities that adopted such zoning practices early, and the degree of housing segregation and disparity in property values in the ensuing decades. [16]

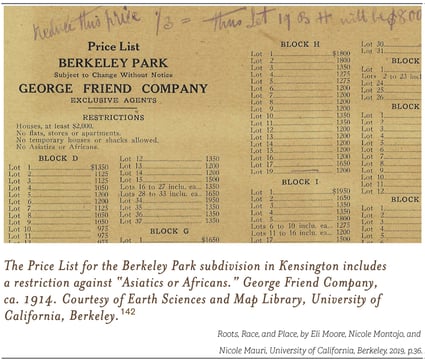

Racial Covenants

Many of our neighborhoods were built upon racially restrictive covenants which were written into property deeds to bar resale – or even rental – based on race. We see it in the history of communities all over our service area. The Whites-only covenant upon which San Lorenzo was built in 1944. The “No Asiatics or Africans” rule that governed the sale of homes in Kensington’s Berkeley Park in 1914. The Laymance Real Estate Company’s 1906 advertisement for Rock Ridge Park in Oakland, promising “no negroes, no Chinese, no Japanese.” [17]

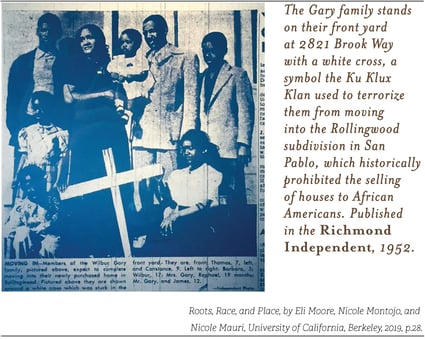

And when the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer Supreme Court decision invalidated racial covenants, communities found other ways to enforce the same effect, continuing “to bar African Americans and other racial minorities from purchasing property in their neighborhoods by creating community associations in which potential buyers would have to become members before purchasing property in the area” – associations with Whites-only memberships.

Racial Steering in Real Estate

In many instances, though, the real estate industry needed no encouragement to maintain a segregated Bay Area. “Racial steering” was one avenue through which realtors might maintain the racial housing landscape, by discouraging Black prospective homebuyers from White neighborhoods – some even admitting to “artificially raising prices for African American prospective buyers, outright refusing to show them homes, and lying about the availability of properties.” Racial steering was reported to be widespread in the area in the 1960s, including within our service area in places like San Leandro and northern Santa Clara County. [18]

Perhaps even more calculated was the practice of “blockbusting,” whereby realtors would stoke racial fears for profit. On one end, a realtor might whip up panic in a mostly-White community about impending integration and a resulting drop in property values – motivating these homeowners to sell. On the other end, they could turn around and sell these homes at a premium to Black buyers – reinforcing segregated housing while collecting additional commissions in the offing. The post-war decades saw blockbusting and racial steering throughout our service area, and the effects were stark in terms of segregation. “In San Jose and surrounding areas, surveys of the rental market revealed that just one in 15 apartments for rent would be open to a Black tenant… In numerous jurisdictions in the East Bay the Black population did not rise above a half of a percent through the early 1970s, including Walnut Creek, Lafayette, San Leandro, Pleasanton, and San Lorenzo.” [19]

Building Forward After the Fair Housing Act

What to do with the heaviness of this history?

What to do with the heaviness of this history?

We must learn our lessons from it, but not simply as a cautionary tale. We must wrestle with the idea that our communities are a product of this history, and its effects reverberate loudly today. So, too, are current patterns of gentrification and displacement that distinctly align with the redlining maps of old. Public health implications continue to disproportionately impact communities of color, who are likelier because of housing segregation to reside near environmental hazards and away from community amenities. And housing discrimination persists, as evidenced by events like a 2016 case against an apartment complex in Santa Clara, settled amid claims that their application process discriminated against applicants of Mexican national origin. [20]

So, we observe Fair Housing Month with clear-eyed commitment. We recognize that housing discrimination may long be illegal, but its practice persists in insidious forms – and its effects remain evident and profound.

We look back so that we might build forward, toward a future where neighbor is not divided from neighbor and opportunity is not rationed upon the pernicious legacy of an inequitable history. So that we might fully honor the ideal of the Fair Housing Act. We are in this together. Habitat for Humanity is built on that reality, on the vision of the community we can be and the community that must come together to build it.

Stay with us as we continue this series into May, Affordable Housing Month, with a spotlight on the city of Richmond – to examine how choices made during a wartime demographic shift set up housing equity that persists today.

[1] “History of Fair Housing - HUD.” HUD.gov / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/aboutfheo/history#:~:text=The%201968%20Act%20expanded%20on,Housing%20Act%20(of%201968).

[2] Rothstein, Richard. “If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 3. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[3] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 15. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[4] Rothstein, Richard. Preface. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, viii. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[5] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 8-9. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[6] Kopf, Dan. The Great Migration of African Americans to the Bay Area. The Golden Stats Warrior, February 26, 2020. https://goldenstatswarrior.substack.com/p/the-great-migration-of-african-americans.

[7] Kamiya, Gary. “When WWII Brought Blacks to the East Bay, White Fought for Segregation.” San Francisco Chronicle, November 23, 2018.

[8] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 39-40. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[9] Kamiya, Gary. “When WWII Brought Blacks to the East Bay, White Fought for Segregation.” San Francisco Chronicle, November 23, 2018.

[10] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 43-44. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[11] Ibid., 45-47.

[12] Rothstein, Richard. “’Own Your Own Home’” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 64-65. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[13] Ibid., 64-67.

[14] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 29. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[15] Weiss, Marc A. “Urban Land Developers and the Origins of Zoning Laws: The Case of Berkeley.” Berkeley Planning Journal 3, no. 1 (2012): 11–20. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/26b8d8zh.

[16] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 31-32. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[17] Ibid., 35-36.

[18] Ibid., 49-51.

[19] Ibid., 51-52.

[20] Ibid., 59-61.

Join the Conversation

Leave Us a Comment!

We love hearing from our community. Let us know what you think by leaving us a comment below.