Richmond: Wartime Work and Unfair Housing

May 4, 2023 Habitat News

Contra Costa County: A Demographic Overview

With 19 cities and additional unincorporated regions, Contra Costa County exhibits “stark racial segregation.” [i] In one part of the county, you see cities like Walnut Creek, Lafayette, and Martinez – “the most segregated and heavily white cities… which epitomize the affluent white suburb.” Then, at the western limit of the county lie Richmond and North Richmond, whose “neighborhoods are highly segregated by race, especially for Latinos and African Americans. Richmond is currently “18 percent African American, 17 percent white, 13 percent Asian, and 48 percent Latino” – proportions far out of step with the county’s demographics at large, and an indication of how highly concentrated Black and Latino residents are in these two cities. [ii]

These demographic patterns have their roots in a time when Richmond and North Richmond saw a period of sudden and rapid shift in demographics – and the way these changes were handled set up a housing equity crisis we still see today. That change was brought about by the onset of World War II.

The War that Transformed Richmond

The War that Transformed Richmond

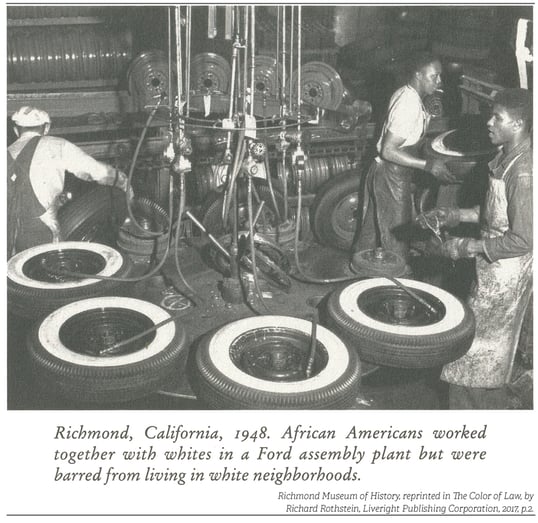

Frank Stevenson was one of thousands of Black people who migrated to Richmond from the south during World War II, in a massive population boom and seismic shift in demographics. It’s with Mr. Stevenson that Richard Rothstein opens and closes The Color of Law, and his story is a telling example.

“Black people migrated to Richmond in search of war-time employment and fleeing the second resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and widespread lynchings in the US South,” according to Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond. “In 1930, there were only 38 Black residents living in Richmond. By the end of World War II Richmond’s Black population was 14,000.” [iii]

Separate and Unequal Housing

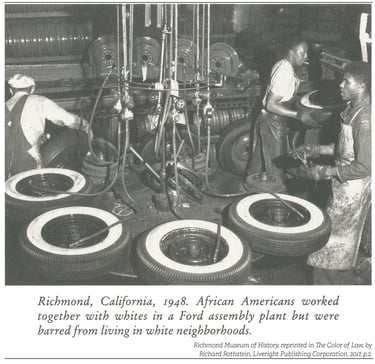

The “influx of war workers” exploded Richmond’s overall population to over four times its pre-war numbers. It meant a sudden and dire shortage of housing, and the federal government responded with “officially and explicitly segregated” public housing. Units built for Black workers were “poorly constructed and intended to be temporary,” and “located along railroad tracks and close to the shipbuilding area.” For White workers, “government housing was built farther inland, closer to white residential areas, and some of it was sturdily constructed and permanent.” [iv]

The “influx of war workers” exploded Richmond’s overall population to over four times its pre-war numbers. It meant a sudden and dire shortage of housing, and the federal government responded with “officially and explicitly segregated” public housing. Units built for Black workers were “poorly constructed and intended to be temporary,” and “located along railroad tracks and close to the shipbuilding area.” For White workers, “government housing was built farther inland, closer to white residential areas, and some of it was sturdily constructed and permanent.” [iv]

Not only was public housing segregated, but White workers also had other housing options that were not open to their Black compatriots. The federal government’s “war guest” program, which enabled war workers to rent rooms in the private homes of Richmond’s White families, was only open to White workers – and the White homeowners were incentivized through low-interest government loans. Further, the government approved bank financing for the construction of suburban Rollingwood, with the stipulation that “none of Rollingwood’s 700 houses be sold to an African American.” [v]

Housing availability for Black workers was made worse by poorly-designed quotas. Local housing authorities allocated public housing according to the demographics of the war workers as a whole – instead of the demographics of those who actually needed public housing. So, they failed to account “for the disproportionate need among Black migrants whose options outside of public housing were far more constrained… The inadequate supply of housing for Black families required many to double up or illegally sublet, which, if found by the housing authority, was grounds for eviction.” [vi]

North Richmond: An Inadequate Alternative

With so few public housing units available to Black workers, many moved to unincorporated North Richmond – Frank Stevenson was one example. As it was unincorporated, residents here were living without access to city services and with scant political representation. [vii]

Richmond’s racial covenants (found as late as 1963) restricted Black residents to purchase in North Richmond, where they might use their wages to buy small lots zoned at 25 feet wide. (All-White Atchison Village, by contrast, had a 20-foot distance between homes.) [viii] Should they purchase land in North Richmond, however, Black residents were unable to access government-insured bank loans, and so were unable to afford standard construction. As a result, “some built their own dwellings with orange crates or scrap lumber scoured from the shipyards. By the early 1950s, some 4,000 African Americans in North Richmond were still living in these makeshift homes.” [ix]

The Demolition of Public Housing Post-War

The Demolition of Public Housing Post-War

More and more White families took advantage of federal programs and moved out of public housing. Meanwhile, “formerly race-restricted units were made available to Black families.” [x] Post-war, the backlash to public housing became intense and resulted in the destruction of housing and the displacement of many Black families.

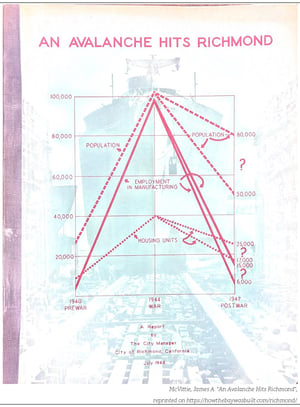

The backlash began with a fixation on the “blight” of public housing and was explicitly laid out in 1949, with the City Planning Commission’s Master Plan for Housing and Redevelopment. The plan outlines the benefits of various types of housing – unavailable to Black residents at the time – such as single-family homes that were “responsible for the quality and attractiveness of the typical residential neighborhoods of Richmond” and other permanent housing projects whose sites were “large and well planned, with space for children’s play areas, automobile parking, safe and quiet streets, open lawns and attractive planting.” On the other hand, the plan describes temporary public housing, primarily occupied by Black residents, as “not conducive to good living,” and adds that “intermingling of temporary housing buildings with private residences is also detrimental to both.” The plan goes on to warn that “slums and blight appear in some sections of the City in the fringe areas outside its boundaries, casting a dark shadow over good property.”

“If these public housing units are allowed to remain after the war need for them is passed, they will not only be a threat to future home building, but will undermine the values of existing private homes in Richmond,” laments Richmond’s City Manager in a July 1944 report. [xii]

The Housing Plan makes an impassioned case for the “protection for single-family neighborhoods,” arguing that “the long-established ideals of America are represented in these neighborhoods of small, pleasant, single-family homes” and that they merit “the utmost official support and protection.” One of the suggested measures is to “control home occupations and operations of boarding and lodging houses to maintain the harmonious residential character of neighborhoods” – a thinly coded call for racial segregation. [xii]

"Urban Renewal" and Displacement

"Urban Renewal" and Displacement

And so, what followed was the mass displacement of Black Richmond residents. The city “abandoned plans to build over 4,000 permanent public housing units to pursue industrial growth.” What’s more, demolition primarily targeted developments occupied largely by Black families. Richmond had “around 80 percent of the Black community liv[ing] in temporary war housing that was then demolished in 1953 through ‘Urban Renewal’ programs.” [xiii] As much of this housing was not replaced – nor was a viable relocation option offered – “over 700 Black families were displaced from their homes in 1952, only 16 percent of whom were able to find housing in the private market. Thousands of former public housing residents lost their homes by 1960.” [xiv]

After the wave of urban renewal, Black residents had little to no housing options and many were forced into “segregated and underresourced neighborhoods, into predatory housing schemes (blockbusting), or directly into violent attacks from white residents.” [xv]

The Ripple Effect

You can see the foundations of today’s housing crisis in the early segregation and financial inequity of Richmond, according to Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond – and they are facets that are familiar throughout the Bay Area. Before the 2008 foreclosure crisis, “Black and Latino homebuyers were over three times more likely to receive risky loans than white borrowers, even with similar credit scores and income.” Housing for low- and very low-income residents is being built entirely in low-resource neighborhoods. A disproportionate number of Black and Latino households are renters. Historic racial exclusion from homeownership is the “single biggest factor in the racial wealth gap,” underlying the fact that “the average white household wealth is seven times that of Black wealth and five times that of Latino wealth.” [xvi] It is a key reason that Habitat remains so focused on expanding access to affordable homeownership.

Much as they were segregated into neighborhoods in years past, Black residents are now being displaced from their historic neighborhoods in Richmond – “the Black population has fallen from 36,600 in the year 2000 to 23,5000 in the year 2015 (a 36 percent decrease).” [xvi]

Frank Stevenson and his wife raised three daughters in a “segregated Richmond neighborhood,” Richard Rothstein reveals at the conclusion of The Color of Law. The Stevenson daughters attended largely segregated schools – segregated due to already-segregated neighborhoods, with added help from the school district and area voters. So much opportunity was rationed along the lines of that housing segregation. What possibilities were lost to this family, Rothstein wonders, as a result of unfair housing policies? And at Habitat, we ask: how do we, together with our community, make it right?

When the Ford Motor Company, Frank Stevenson’s employer, moved its operations from Richmond to Milpitas in 1953, it meant hundreds of jobs moved with it. However, Mr. Stevenson did not find a home in Milpitas. Learn more in our next highlight.

[i] Menendian, Stephen, and Samir Gambhir. Publication. Racial Segregation in the San Francisco Bay Area, Part 1. University of California, Berkeley, October 30, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/racial-segregation-san-francisco-bay-area-part-1.

[ii] Ibid., 11-12.

[iii] Bissell, Evan, Eli Moore, Heather Broomfield, Sarah Brundage, William Edwards, DeAndre Evans, Ciera-Jevae Gordon, et al. Rep. Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond. Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, January 26, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/housing-policy-and-belonging-richmond.

[iv] Rothstein, Richard. “If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 5. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[v] Ibid., 6.

[vi] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 40. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[vii] Bissell, Evan, Eli Moore, Heather Broomfield, Sarah Brundage, William Edwards, DeAndre Evans, Ciera-Jevae Gordon, et al. Rep. Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond. Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, January 26, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/housing-policy-and-belonging-richmond.

[viii] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 40. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[ix] Rothstein, Richard. “If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 7. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[x] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 40. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[xi] McVittie, James A., An Avalanche Hits Richmond: A study of the impact of war production upon the City of Richmond, California, and an outline of measures necessary to provide the facilities for normal postwar community service, a report (1944).

[xii] White, Albert C., Housing and Redevelopment: The Master Plan of Richmond, California, (1949).

[xiii] Bissell, Evan, Eli Moore, Heather Broomfield, Sarah Brundage, William Edwards, DeAndre Evans, Ciera-Jevae Gordon, et al. Rep. Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond. Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, January 26, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/housing-policy-and-belonging-richmond.

[xiv] Moore, Eli, Nicole Montojo, and Nicole Mauri. Rep. Roots, Race, and Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 41. Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, 2019.

[xv] Bissell, Evan, Eli Moore, Heather Broomfield, Sarah Brundage, William Edwards, DeAndre Evans, Ciera-Jevae Gordon, et al. Rep. Housing Policy and Belonging in Richmond. Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, January 26, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/housing-policy-and-belonging-richmond.

[xvi] Ibid., 57.

Join the Conversation

Leave Us a Comment!

We love hearing from our community. Let us know what you think by leaving us a comment below.