Milpitas: A Study in Systemic Exclusion

May 10, 2023 Habitat News

Santa Clara County: A Demographic Overview

Today, Santa Clara County is known for the innovation of Silicon Valley, making this “one of the most economically prosperous counties in the United States.” Even so, “its neighborhoods and communities remain remarkably segregated.” The county contains some of the most segregated neighborhoods for Latinos and Asians, for example. [i]

Santa Clara County is the Bay Area’s most populous, but it “had barely 40,000 Black residents as of 2010” – just about 2.5% of nearly 1.8 million residents that year. On the other hand, with the 1960 Immigration Act came “a large influx of South Asian and East Asian immigrants… As a result, a number of historical neighborhoods received a large number of first-generation immigrants, while third- and fourth-generation immigrants moved elsewhere.” One of those places was Milpitas, which today has the county’s highest proportion of Asian American residents – about two-thirds. Like the rest of the county, the population of Milpitas is largely segregated, with 11 of its 15 census tracts exhibiting “high segregation.” [ii]

And the story of Milpitas is marked, at the outset, by segregated housing.

Ford Moves to Milpitas

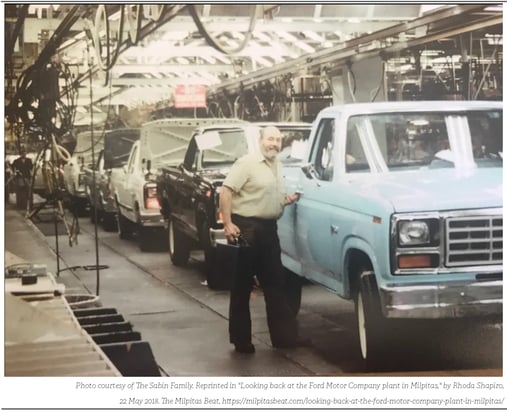

In 1953, Ford Motor Company’s relocated their assembly plant in Richmond to a 160-acre site in the rural township of Milpitas, 50 miles south. However, Black workers found that no warm welcome waited in Milpitas when it came to housing. [iii]

In 1953, Ford Motor Company’s relocated their assembly plant in Richmond to a 160-acre site in the rural township of Milpitas, 50 miles south. However, Black workers found that no warm welcome waited in Milpitas when it came to housing. [iii]

The residents of Milpitas, anticipating the influx of newcomers, incorporated into a city and hastily “passed an emergency ordinance permitting the newly installed city council to ban apartment construction and allow only single-family homes.” This effectively made housing stock off-limits to Black residents. Single-family homes were being built with FHA-backed construction loans, and “one of the federal government’s specifications for mortgages insured in Milpitas was an openly stated prohibition on sales to African Americans.” And so, with their plant relocating to a city without rentals – and homes they could not purchase – Black workers “had to choose between giving up their good industrial jobs, moving to apartments in a segregated neighborhood of San Jose, or enduring lengthy commutes between North Richmond and Milpitas.” Many chose the last option. [iv]

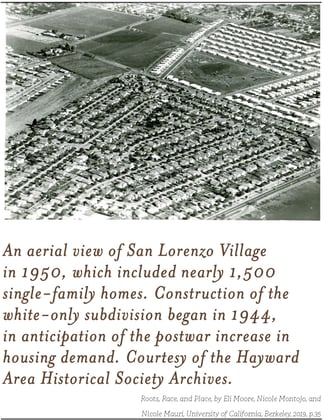

Black workers commuted through miles of housing built for White workers. Developer David Bohannon “created the massive whites-only San Lorenzo Village,” whose sales brochures promised “farsighted protective restrictions… permanently safeguard your investment” – a reference to racial covenants in their deeds that prevented resale to Black buyers. [v]

David Bohannon started building Sunnyhills in Milpitas in 1955 – one among a number of Whites-only single-family developments under way in the area.

Integrated Housing Faces Immediate Roadblocks

Integrated Housing Faces Immediate Roadblocks

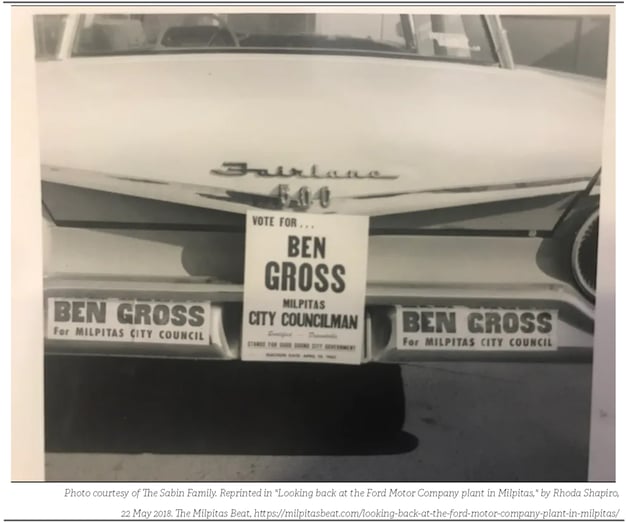

One Black migrant to the Bay Area took on a pivotal role in the struggle for housing in Milpitas. Ben Gross was born in Arkansas in 1921, into the Jim Crow south. Gross moved to Richmond and found work at the Ford plant in 1949. There, he joined the United Auto Workers union and become active in union politics. “In 1950 he became the first African American elected to Local 560’s bargaining committee,” and four years later, he was appointed Local 560’s housing committee chairman. [vi]

Ford’s move to Milpitas brought the new housing chair an uphill challenge. Gross worked with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a “Quaker group committed to racial integration,” and met with roadblock after roadblock. They tried to convince local developers to sell any of their overbuilt inventory to Black residents – and they were turned down. They attempted to recruit a new developer that would build an integrated community – and ran into a startling array of plots designed to preserve housing segregation.

Persistent Pushback

Finding construction financing for an integrated development proved nearly impossible, until the AFSC made a personal plea to a fellow Quaker at the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company – and they agreed to a loan. However, when the county Board of Supervisors caught wind of the plans for an integrated community, they re-zoned the planned site for industrial use. The group tried another site in Mountain View, but they were informed by officials that they would not be granted approvals. A third site near the plant fell through: “when officials discovered that the project would not be segregated, the town adopted a new zoning law increasing the minimum lot size from 6,000 to 8,000 square feet, making the project unfeasible for working-class buyers.” The fourth site was likewise thwarted, when the land seller canceled upon learning the development would be integrated.

Finding construction financing for an integrated development proved nearly impossible, until the AFSC made a personal plea to a fellow Quaker at the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company – and they agreed to a loan. However, when the county Board of Supervisors caught wind of the plans for an integrated community, they re-zoned the planned site for industrial use. The group tried another site in Mountain View, but they were informed by officials that they would not be granted approvals. A third site near the plant fell through: “when officials discovered that the project would not be segregated, the town adopted a new zoning law increasing the minimum lot size from 6,000 to 8,000 square feet, making the project unfeasible for working-class buyers.” The fourth site was likewise thwarted, when the land seller canceled upon learning the development would be integrated.

A glimmer of hope arrived when a San Jose businessman purchased the lot next to Sunnyhills, the all-White community under development by David Bohannon – a businessman willing to work with the UAW and AFSC on an integrated neighborhood to be known as Agua Caliente. Bohannon’s company appealed to the Milpitas City Council to put a stop to it “by denying it access to sewer lines.” [vii]

As a result, the sanitary district board “held an emergency meeting and adopted an ordinance that increased the sewer connection fee by more than ten times”—which halted work on Agua Caliente. Although the builder eventually agreed to continue, Bohannon’s company levied a nuisance lawsuit to keep Agua Caliente from proceeding. Finally, with the accumulating delays and legal bills, the UAW’s builder could not continue. [viii]

The Long Fight for a Small Victory

Ben Gross and the UAW – along with the AFSC – were not to be deterred, however. The union publicly campaigned against Sunnyhills and boycotted purchase of homes there, and “they flooded open houses to disrupt sales to white buyers.” They also reached out to the state’s attorney general to investigate the hike in sewer connection fees. At last, Bohannon’s company walked away.

The UAW found a new developer who bought out both projects, and an integrated project was built under the single name of Sunnyhills. Without the FHA’s backing, mortgages were still a problem. Eventually, though, the FHA “agreed to guarantee mortgages with a favorable rate only if the subdivision were converted to a cooperative, in which the owners would possess shares of the overall project rather than their individual houses” – to which the union agreed. [ix]

The victory, though incredibly symbolic, was limited in its impact at the time. When the homes were finally available, the Ford plant was well into operation, and most transferred workers had made accommodations – whether it was White workers taking up any of a number of housing options open to them, or Black workers resolving to other avenues. For many who remained, Sunnyhills proved too expensive due to the numerous obstacles that had raised its cost. [x]

Echoes of Sunnyhills

Echoes of Sunnyhills

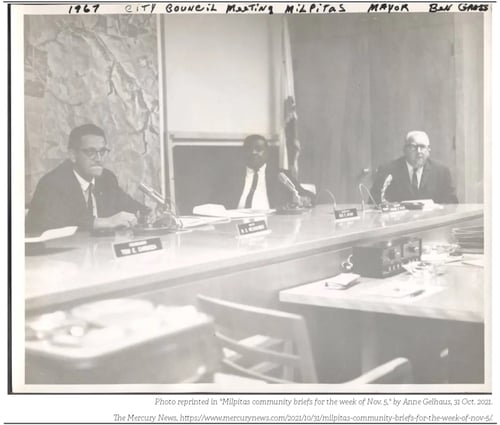

Sunnyhills is known as “the first planned interracial community in America sponsored by a labor union.” Ben Gross went on to become, in 1961, the first Black city council member in Milpitas. In 1966, he was elected mayor – making him unique throughout the state at the time as a Black mayor of a predominantly-White city. [xi]

In Milpitas, Sunnyhills will still “evoke a slew of memories. Back in the day, the Sunnyhills neighborhood was where it all happened. It was a hub of activity and progress, a kind of engine that set the wheels of a small, still relatively unknown town in motion… For so many who grew up in Sunnyhills, their childhoods were marked by a deep sense of purpose, inclusion, and transformation.” [xii]

Milpitas still bears the scars of its early resistance to integration. “In the ensuing years,” Rothstein points out, “African American residence in Milpitas continued to be confined to Sunnyhills and a relatively undesirable project, built in the 1960s between two freeways and a heavily trafficked main shopping thoroughfare.” And today, although it has diversified with respect to other non-White residents, “African Americans make up only 2 percent of the population.” [xiii]

Milpitas is just one among many cases in point for our region’s struggle with fair housing. What happened in Milpitas “illustrates the extraordinary creativity that government officials at all levels displayed when they were motivated to prevent the movement of African Americans into white neighborhoods.”[xiv] For us at Habitat, this story is a reason to celebrate the Fair Housing Act – whose passage could have changed the course of this early fight for housing. But, it is also a reminder to be ever-vigilant for the ways in which the Fair Housing Act can be subverted.

Next in our Fair Housing series, we take a look back to West Oakland and a pivotal moment in fair housing history there.

[i] Menendian, Stephen, and Samir Gambhir. Publication. Racial Segregation in the San Francisco Bay Area, Part 1. University of California, Berkeley, October 30, 2018. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/racial-segregation-san-francisco-bay-area-part-1.

[ii] Menendian, Stephen, and Samir Gambhir. Publication. Racial Segregation in the San Francisco Bay Area, Part 2. University of California, Berkeley, February 7, 2019. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/racial-segregation-san-francisco-bay-area-part-2.

[iii] Rothstein, Richard. “If San Francisco, Then Everywhere?” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 9. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[iv] Ibid., 9-10.

[v] Rothstein, Richard. “Local Tactics.” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 115-116. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[vi] Ruffin, Herbert G. “Ben Gross (1921- ) .” Ben Gross. BlackPast.org, July 25, 2020. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ben-gross-1921/.

[vii] Rothstein, Richard. “Local Tactics.” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 119. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[viii] Ibid., 120.

[ix] Ibid., 121-122.

[x] Ibid., 122.

[xi] Ruffin, Herbert G. “Ben Gross (1921- ) .” Ben Gross. BlackPast.org, July 25, 2020. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ben-gross-1921/.

[xii] Shapiro, Rhoda. “The Untold Stories of Sunnyhills, Where History Was Made.” The Milpitas Beat, February 14, 2019. https://milpitasbeat.com/the-untold-stories-of-sunnyhills-where-history-was-made/.

[xiii] Rothstein, Richard. “Local Tactics.” Chapter. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 121. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[xiv] Ibid., 122.

Join the Conversation

Leave Us a Comment!

We love hearing from our community. Let us know what you think by leaving us a comment below.